Not surprisingly, during the recent

National Discussion on Health Information Technology and Privacy held on the web, the issue of privacy was at the forefront. The issue of mental health information privacy was of the utmost concern. I discuss the privacy debate in this post, and offer an innovative solution.

Who Should Own One's Personal Health Information?

A knowledgeable participant at the online conference, Laura Groshong, LICSW, Director, Government Relations, Clinical Social Work Association, offered these wise words:

…I don't think patients want to be the 'owner' of all this data, responsible for sending it to the parties who need it and determining who these are. This is part of the flaw in thinking that patients should become the owner, and discloser, of all their medical information.

When it comes to mental health information, there are special problems. HIPAA has an exception about information being shared with patients if the clinician thinks it might cause harm. This is a significant concern for mental health clinicians when the patient is not ready to hear the specifics of how the clinician has diagnosed them. Patients may be aware that they feel understood by the clinician without knowing the way the clinician understands their problems for quite awhile.

Another concern I have about making the patient the owner of his/her records is how this will be implemented by people who may be homeless, incarcerated, unable to understand the disclosure process, or otherwise off the grid of being able to keep track of their own information.

I agree with her comment. It would be foolish for a consumer to dictate whether or not their primary care doctor or medical specialist should be allowed to view their lab results, imaging studies, etc. since it may be a life threatening decision for which consumers are ill-prepared to make. However, they should have control over whether their employers (or others) get to see this type of health information.

I also agree that mental health information is a special case.

For one thing, most mental health information is not life threatening, except, perhaps, suicidal and homicidal ideation/tendencies. When providers have knowledge that such dangerous behavior is likely, they are required to report to authorities (along with and sex and physical abuse). Consumer/patient consent is

not needed.

In any case, I believe consumers should have full ownership/control over whom, if anyone, gets to see any other consumer-generated mental health information. This include information about their cognitions (thoughts, beliefs, perceptions), emotions, behavioral tendencies, psychosocial history, interpersonal relationships, etc. it.

And if some people do not have the capacity to make determinations about sharing their health information, a health proxy (or other "trusted partner") could assist them.

Please realize that I'm not talking about giving mental health consumers access to and control over their providers' session notes, or even giving specific individuals their mental health diagnoses or professional observations prematurely if it is clear such knowledge would cause irreparable harm to the treatment/recovery process. What I am referring to is the information contained in one's personal health record or personal health profile.

So, to me, it's not about having consumers track and control all their health information by disallowing their healthcare providers from accessing essential information needed to make life-saving and wellness decisions. Instead, it's about having control over who gets to see one's mental health information, and who, other than the physician(s) involved in one's care, is authorized to view one's biomedical and genetic information.

Next, I'm going to share some thoughts about the kinds of information that should and shouldn't be under a consumer's direct control. I'll also discuss what to do about it.

Types of Personal Health Information

As I mentioned above, there are some types of personal health information (PHI) that should

not be under the direct control of the consumer, at least not without a warning. And even if consumers have some control over that information, it makes little sense to force them to approve each and every piece of data that is shared with their healthcare providers. Other types of PHI, however, should be under a consumer's complete control…every piece, piece by piece.

Determining PHI control in a logical manner requires dividing the information into different categories by classifying them according to some

taxonomy. These PHI categories are comprised of "data sets," i.e., groups of related data. Rules can then be applied to these data sets, which dictate the way each particular piece of data in that category is controlled.

I will now offer a possible classification scheme, which divides all PHI into these seven categories, each of which contain one for more data sets:

- Personal Identifiers

- Personal Demographics

- Emergency Medical and End-of-Life Information

- Biomedical Health PHI and Genetic Information

- Mental Health PHI

- PHI regarding Physical Activity, Exercise, Nutrition, Energy Levels

- PHI for Research Purposes.

I will also suggest who should, and should not, have access to that information.

1. Personal Identifiers

Personal identifiers include a person's:

- Name

- Address

- Insurance and patient ID numbers

- Other information that can be used to identify the person to whom the PHI refers.

It is important for professionals providing healthcare to a patient, as well as those paying for a patient's care. It should

not be made available to others, however, unless the consumer consents or HIPAA rules demand it. For research purposes, a people's PHI should be de-identified to protect their privacy by removing this data set.

2. Personal Demographics

A person's demographics refer to information that places the individual in a specific group based on such data as:

- Age

- Gender

- Race

- Religion

- Family size

- Level of education

- Occupation

- Income

- Zip code.

Some of these data may be useful in making medical treatment decisions, including one's age, gender, and possibly race. And others may be useful in mental health care. Nevertheless, demographic data are essential for most clinical research.

3. Emergency Medical and End-of-Life Care Information

Emergency medical and end-of-life care information includes such data as:

- Blood type

- Allergies

- Past and current medical conditions

- Current medications and dosages

- Emergency contact information (family and physicians)

- Advanced directives (include living wills and durable powers of attorney).

Any authorized provider delivering care to a person in an emergency ought to have access to this information, even if the person is unable to consent at the time. See

this HIPAA flowchart for more.

4. Biomedical Health PHI and Genetic Information

Biomedical health and genetic PHI includes health history, current health status, health risk information, as well as genetic information. This category contains biomedical and psychological data about a person's:

- Existing symptoms

- Current and past health conditions/problems

- Current and past exams and interventions/treatments

- Risks posing a threat on one's future health status

- Biometrics (e.g., weight, blood pressure, cholesterol levels, vital signs, etc.)

- Imaging studies (e.g., x-rays, CT scans, MRIs, ultrasound, etc.)

- Genetic makeup (of self and family).

Much of this information would be useful for most physicians treating a patient, as well as one's wellness coaches/counselors and others involved with a consumer's physical wellbeing. A one-time consent that authorizes the sharing of such information among one's physicians is justified, as well as allowing a person to authorize other types of practitioners to access specific data in this category.

Note that people with health problems or risks are unlikely to want their employers or health plans (insurers) to have access to this PHI as it may be used to make employment and insurance decisions that are not in their best interests. This issue is complex and includes debates over

whether genetic data should be considered private or proprietary, as well as causing

various ethical dilemmas.

Another issue is whether any of this PHI should be sent to public health agencies if there is reason to believe that a person has a seriously contagious illness, or if there are multiple people in a region with a health problem that indicates a possible outbreak (pandemic, epidemic, or terrorist attack). This issue is addressed by the

HIPAA Privacy Rule and Public Health.

5. Mental Health PHI

Mental health PHI includes all psychological, psychiatric, and psychosocial information. This broad category encompasses information about one's perceptual, emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and social life. It includes a huge diversity of information, such as:

- Excesses of emotion, mood, affect including anger toward others/resentment, anger toward oneself, depression, anxiety, guilt, shame/embarrassment, jealousy/envy, pessimistic about the future, manic periods/emotional excitability, low frustration tolerance, easily irritated/annoyed, impatient, lack of adequate temper control

- Deficits of emotions, mood, affect including lack of pleasure/enjoyment, feelings of boredom/emptiness, flat or grossly inappropriate affect, unawareness of one's emotions, apathy, lack of empathy, remorse, tender emotions, and cool indifference

- Instability of emotions, mood, affect including bipolar symptoms

- Excesses of activity, drive, impulse, behavior including compulsions and restlessness, psychomotor agitation or tension, hyperactivity and poor impulse/urge control, reckless behavior, failure to adequately consider the consequences to one's actions, poor or lack of planning & decision-making, indecisiveness, kleptomania, pathological gambling, pyromania, trichotillomania, compulsive sexual activity, compulsive spending, workaholism

- Deficits of activity, drive, impulse, behavior including poor work effort/motivation, loss of initiative, disinterest, poor planning, failure to persist on task, procrastination, difficulty making decisions, passive-aggressive behavior, irresponsible behavior, psychomotor retardation, lethargy, lack of activities of daily living (ADL) skills

- Eating problems including excessive eating (overeating), poor appetite, excessive dieting or fasting, vomiting or use of laxatives, binging and purging, body weight

- Sleep problems

- Sexual problems and issues including sexual abuse; general information; violent sexual thoughts and fantasizes; sexual dysfunctions

- Physiological symptoms related to one's physiology including gastrointestinal problems, autonomic nervous system symptoms, motor tension and overactivity, cardiopulminary symptoms, motor lethargy, numbness, tingling sensations, paralysis, sexual problems, and more

- Psychosocial stressors and interpersonal problems including family strife, problems with work or school, problems with one's living situation or working environment, legal problems, financial problems, etc.

- Psychoactive substance use including caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and illicit drugs

- Maladaptive cognitive styles on mental symptoms/dysfunctions including ultra-conservatism (avoids constructive risk-taking), pessimism, helplessness, hopelessness, lack of self-efficacy, perfectionism, inflexibility, dogmatic style, preoccupation with organization/order, paranoid ideation (non-delusional), lack of trust, suspiciousness

- Primary dysfunctional cognitive schemas including irrational beliefs, negative self-concept and global self-appraisals, non-delusional inflated appraisals of self such as narcissism, self-centeredness, grandiosity, attention/approval-seeking; manipulative behavior; exhibitionism; negative global appraisals of others/prejudice

- Secondary dysfunctional cognitive schemas including low self-efficacy; pessimistic future expectations; sense of wrongness, unfairness, entitlement/deservingness; causal attributions (responsibility)

- Coping styles

- Maladaptive levels of alertness, attention, concentration, vigilance, concentration (vigilance deficits and attentional excesses)

- Identity problems and confusion including multiple personality symptoms, depersonalization and derealization symptoms, gender-identity problems

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

- Disturbances of consciousness and orientation

- Memory problems and amnesia including psychogenic fugue, immediate and short-term memory impairment, recent and remote memory impairment, paramnesia, general memory impairment information

- Abstract thinking, intelligence, dementia, pseudodementia

- Problems with insight and judgment

- Executive functioning impairment and non-verbal communication learning disabilities (including dyslexia, dyscalculia, dysgraphia, directionality difficulty)

- Disorders of receptive or expressive communication

- Disturbances of thought process and form

- Hallucinations and illusions

- Perceptual agnosias

- Conversion disturbances

- Delusions

- Obsessions

- Peculiar, odd, eccentric behavior or appearance

- Overconcern with body shape or size

- Grossly defective/disorganized behavior

- Self-directed violence/aggression including suicidal and self-mutilation behavior

- Other-directed violence/aggression and anti-social behaviors including violent and non-violent conduct problems

- Interpersonal rejection, avoidance, abandonment, social withdrawal, social anxiety, under socialization, interpersonal indifference, shyness, dependency, passivity, loneliness, insecurity, passivity/unassertiveness, proneness to peer-pressure, pattern of unstable/poor relationships

- Defense mechanisms employed including mature defenses, neurotic defenses, immature defenses, and narcissistic defenses

- Early (childhood) psycho-social experiences

- Factitious disorders.

Is it worth computerizing such mental health information? I say YES it is because

failure to digitize and share such PHI:

- Prevents the mental health field from developing its potential (e.g., by not allowing de-identified data "from the field" to be used to the study and improve treatment effectiveness)

- May increase risk (e.g., makes it difficult to do an assessment of medication side effects, especially if multiple medications are taken)

- Keeps a wealth of consumer-generated information from being used for treatment planning and delivery

- Prevents consumers from taking advantage of a new generation of computerized self-help tools that increase self-understanding, and offer help with coping and problem solving

- Makes it nearly impossible to deliver care through a "whole-person" (mind & body) approach.

At the same time, failure to protect a person's psychological information is destructive and simply unacceptable, whether it is in electronic or paper form.

So, who should be authorized to access a consumer's mental health PHI? Well, it depends on what the particular information is in this category.

It is no surprise that mental health practitioners would benefit from having access to the vast majority of this information since it is helpful with treatment planning and delivery. They would also benefit from combining this information with the certain biomedical and genetic information (e.g., to determine if medication side-effects or medical illnesses are presenting as or exacerbating one's physiological symptoms, to understand if psychological stress or emotional distress are adversely affecting one's physiology, etc.).

Integrating some of this mental health information with their patients' biomedical information would also benefit non-psychiatric physicians and other non-mental health providers by helping them understand their patients' health status and needs in an integrated whole-person manner that encompasses both the mind and body. This comprehensive information would, for example, help these professionals:

- Determine if there are adverse side effects of medications taken, which present as psychological symptoms

- Gain insights into their patients' motivation and ability to self-manage acute and chronic conditions

- Be aware when psychological problems are adversely affecting their patients' physical health; for example:

- There is a strong connection between optimism, coping skills, and physical health. Researchers found that depression is a precursor to heart disease, with certain depressed patients being 50 percent more likely to develop or die from heart disease than those without such symptoms, even though they had no prior history of heart disease. Depression, therefore, likely affects not only the mind but also physical health by being linked to increased blood pressure and abnormal heart rhythms, as well as chronically elevated stress hormone levels, which can increase the heart's workload.

- Disturbances of physiology that are related in some way to situational/psychological conditions, but without actual permanent end-organ damage, include migraines, functional bowel disease and types of chronic pain. And disturbances where actual physiological and psychological pathologies are evident include hypertension, peptic-ulcer disease, hyperthyroidism, asthma and chronic skin disorders.

- As many as 25 percent of all outpatient visits can be accounted for by psychological factors that cause physiological disturbance with no permanent organ damage (as in migraines, functional bowel disease, and types of chronic pain). That's the narrow definition of psychosomatic illness. The percentage rises to around 50 percent of all ambulatory care if the definition is expanded to include conditions where actual physiological changes occur (such as in hypertension, hyperthyroidism, asthma, and chronic skin disorders). The percentage rises even higher when the definition of psychosomatic is widened to include serious physiological disorders, such as autoimmune disturbances that tend to appear or flare up with significant life changes and stress.

- Knowing when psychological problems are adversely affecting a patient's physical health helps a provider determine when to make a referral to a mental health professional. This is important because:

- Psychological interventions are becoming a necessary component of treatment, or even the treatment of choice, for many psychophysiological (mind-body) disorders. When mental healthcare specialists render treatment for psychological disorders, such as depression, patients realize better outcomes for lower cost compared to treatment delivered in general medical practice.

- Research demonstrates that behavioral healthcare enhances physical health, raises the body's ability to recover from illness and surgery, and prevents biological illness by helping to alleviate stress, promote physically healthy lifestyles, and strengthen the immune system.

- There is a wealth of research demonstrating how the treatment of psychological and behavioral aspects of illness decrease medical utilization and costs, which can more than offset the cost of providing the behavioral interventions, resulting in total cost savings. An example of this "medical cost offset effect" is research that found attending to the psychological needs of patients diagnosed with somatization disorder reduces the annual cost of their medical care by almost one-third.

Now to the question: Who should control a consumer's mental health information? I assert that it should be the consumer him/herself, and the information should be controlled at a granular level of detail. That is, the consumer should determine who is authorized to view each piece of data, andeveryone else should be blocked from seeing it.

6. PHI regarding Physical Activity, Exercise, Nutrition, Energy Levels

PHI regarding one's level of physical activity, degree of exercise, nutrition, and energy drains and boosters would be useful to all healthcare providers, and at would be key information for wellness coaches/counselors.

7. PHI for Research Purposes

All the PHI data sets above would be useful for different types of clinical research. Since personal identifiers are not necessary for this type of aggregate analysis, the data should be de-identified before being sent for research. If the person's identity is guaranteed protected, I don't see an urgent need for authorization, although it will likely be required. I'd even go so far as to recommend that consumers and their healthcare providers be paid by those using their PHI for research, even when the information is de-identified. I say this because such payments may promote greater use of electronic health record systems in general, as well as support research efforts.

How Consumers can Control their PHI

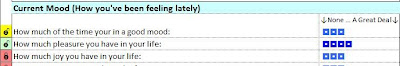

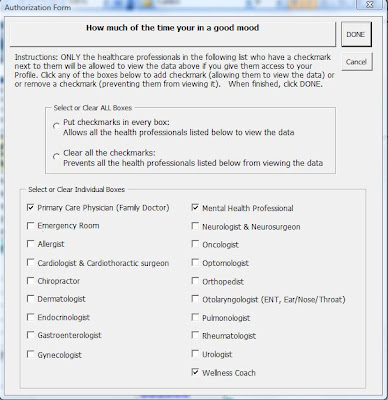

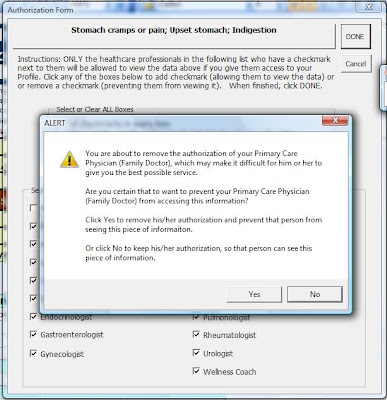

There are at least two mechanisms by which consumers can control their digitized PHI: Use of limited data sets and granular authorization controls.

Limited Data Set Control

One method is to predefine "limited data sets" in which only a particular sub-sets of PHI in the categories discussed above shared with particular types of authorized persons. In some cases a consumer would have to consent

only one time to authorize particular healthcare professionals to access and share their PHI. In other cases, no consumer consent may be required (e.g., for the protection of public health). And in still others, consent may be required every time.

These data sets may include information from one or multiple PHI categories. Note that there may be times to allow a consumer to override a limited data set in order to restrict access to particular pieces of data.

To make all this happen, a health information technology tool must automatically manage a variety of rules that define the data sets, authorize the appropriate recipients, and give a consumer the ability to override the rules when appropriate.

Granular Authorization Control

Granular authorization control means giving a consumer the ability to authorize access to certain types of healthcare professionals, and prevent access from others, for each and every piece of data in the various PHI categories. This may include overriding certain limited data sets, as well as having complete control of all other data sets.

For convenience sake, the consumer should be able to authorization each piece one time, and then be able to update the authorizations whenever desired. In addition, if a consumer fails to authorize certain providers of specific information they need to do their jobs effectively, or if s/he removes the prior authorization of those professionals, a warning should appear informing the consumer that this action is unwise. Likewise, if the consumer (mistakenly) authorizes certain provides to access certain sensitive data they do not need, another alert should appear letting him/her know what is being done.

Combined Control in Personal Health Records/Profiles

When it comes to personal health records (PHRs), there ought to be combined controls. That is, a consumer ought to be able to implement a one-time authorization of limited data sets for certain PHI, as well as authorizing the rest of their PHI via granular control, and be guided by the warnings and alerts as describe above. This means the consumer needs a clear-cut way to recognize the authorization status of each piece of data in every PHI category, and to be instructed along the way.

I know of no PHR that has these capabilities. However, the personal health profile we've developed already does it!

See this link for more.